How a ‘mashgicha’ religious fertility supervisor watches over lab eggs and sperm to make sure there are no mix-ups.

Sometimes, when Esther Friedman is walking down the busy streets of Borough Park, Brooklyn, she might see a former fertility patient on, say, 18th Avenue, and freeze. What should she do: stop and say hi? Smile politely and keep walking? Most of the time, she errs on the side of privacy and pretends that she doesn’t know the woman or her kids, even if she basically witnessed their conception.

Mrs. Friedman, as the sexagenarian likes to be called, is many things—a doula, a sewing teacher, a volunteer preparing Shabbat meals for people at the hospital and a professional baby cuddler—but she’s not a doctor, nurse or other professional with medical training. She’s an IVF mashgicha—a supervisor who ensures that the fertility treatments are going according to plan.

Fertility treatments have become so widespread in Orthodox communities that some rabbis now claim they are an obligation. Like all other aspects of observant Jewish life, the medical procedures also entail a set of religious rules. Many Orthodox rabbis require people utilizing in vitro fertilization (IVF) to have a designated Jewish supervisor present in the laboratory every time a gamete (sperm, eggs, embryo) is handled. Some rabbis say the supervisor’s role is to ensure the gamete belongs to the couple in treatment while others emphasize the practice as a way to establish Jewish lineage. But whatever the reason, it’s increasingly common for Jewish couples to request an observer in the IVF lab.

That observer is known as an IVF mashgicha—the feminine version of the Hebrew word mashgiach, which traditionally refers to the man who certifies the kosher status of food. For the last 25 years, Friedman has worked at Genesis Fertility and Reproductive Medicine, an IVF clinic serving a mostly observant Jewish community in Boro Park. She reports to the head rabbi of Brooklyn’s Maimonides hospital complex (under which Genesis operates), Rabbi Avrum Friedlander.

“Hashgacha (supervision) services opens up fertility care for couples who otherwise would be locked out,” said Dr. Richard Grazi, founding director at Genesis and author of the book Overcoming Infertility: A Guide for Jewish Couples. As far back as 1997, The New York Times was reporting on the controversy over IVF among Orthodox Jews who were caught between their desire and sense of duty to have children, and their ambivalence toward intrusive medical interventions. Much of the ambivalence, according to the Times, stemmed from the fear “that a laboratory mix-up will lead to the insemination of the egg by a stranger’s sperm.” Two decades ago, the solution was to post a rabbi in the lab to keep watch, but today the role is typically carried out by religious women deputized by rabbinic authorities to act as mashigchas.

Public cases of embryo mix-ups, although not common, make headlines every few years that send chills down the spines of new parents and couples trying to get pregnant. The issue came to light last year in the story of a Queens mother who went through an IVF cycle that resulted in her becoming pregnant and giving birth to twin boys only to discover that the babies were not genetically related to each other, and neither boy was related to her or her husband. The birth mother only became aware of the mix-up because she and her husband were both Asian, while neither of the boys she delivered appeared to be. That highlights an uncomfortable fact: “More of these serious mix-ups likely go unnoticed, especially if there is no obvious racial mismatch,” as an article in The Atlantic put it last year. Meaning, even if they are extremely rare, the true number of cases is impossible to know without forcing genetic tests on new mothers. Without any kind of federal regulation or other legal oversight, the religious practice of using mashgichot, offers a seemingly old-fashioned solution to a modern problem.

“Hello!” Friedman joyously called out as she entered the waiting room of Genesis clinic. With her blondish sheitel bangs and black and gold owl-shaped glasses, the pretty 65-year-old was primly yet decoratively dressed in a pleated skirt and thick nude stockings—an outfit customary for the Satmar Hasidic community to which she belongs. She topped it with a loose black sweater decorated with mountain scenery, and a chunky, bejeweled necklace.

She beckoned me upstairs to the embryology lab, where she waited for her patient to arrive.

It was hard for me to believe that even after four years of fertility treatment at six different fertility clinics in three countries (not to mention five pregnancies, only the last one of which resulted in a baby), and reporting on it all for outlets like The New York Times, I had never actually been inside a fertility clinic’s lab.

“You’re only as good as your lab,” I’ve heard it said, referring to a clinic’s embryology and andrology lab—where embryos and sperm are handled.

Obviously, reproductive endocrinologists (fertility doctors) are essential to a patient’s success, as is the patient’s diagnosis and profile. (That’s a euphemistic way of referring to a woman’s age, which is “the single most important factor in predicting success with [fertility] treatment,” according to The Journal of Human Reproductive Sciences).

Yet it is the lab and its embryologists that really make the difference between a “take-home” baby (as they sometimes call a live birth), and more fertility treatments. “We are the heart of the practice,” Dr. Alka Goyal, lab director at Genesis, later tells me.” But we are never in the limelight.”

That’s the problem with IVF labs. As crucial as they are, we patients have no way of knowing what happens there.

Most IVF clinics in the United States report their success rates to the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology (SART), including how many cycles they do per year, how many result in pregnancy, divided by age group and type of pregnancy (chemical, clinical, live-birth, singleton, twins or more). But it’s really hard to assess how good a lab is, because the accreditation process and evaluation by the College of American Pathologists (embryology) and Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (andrology) is not public.

That’s why I wanted to get inside so I could actually see the assisted reproductive technology, which helps subfertile couples get pregnant, either by inserting sperm into the uterus (IUI), or extracting a woman’s eggs and fertilizing them with sperm in the lab, and then, transferring those resulting embryos back into her womb (IVF). I did both, many, many times but I was only involved at the clinical level, taking hormones to increase my egg production, undergoing semiweekly ultrasounds and blood tests to determine when my eggs would be retrieved. After they were extracted, and my husband produced his sperm, both eggs and sperm were whisked off to the lab. And until the embryo transfer three to five days later, the rest was a mystery.

I knew a lot had to happen behind those closed doors: The sperm and eggs must be prepped to meet in a petri dish for IVF. The eggs need to be examined to ascertain which ones are mature (alive and ready for fertilization), and sometimes one sperm needs to be extracted from the semen (if it’s paltry or slow) and injected into the egg for ICSI (instead of placed in the petri dish for normal fertilization). After fertilization, embryologists need to take the embryos out of the incubators every other day to check on their progress (although some incubators have cameras inside, obviating that step). And then, the 5-day-old embryos may need to be biopsied, where a cell or two is sent off for chromosomal testing before transfer.

In other words, the sperm, eggs, and resulting embryos are handled a lot in the laboratory. And if you’re religious and need supervision, an IVF mashgicha has to be there every step of the way.

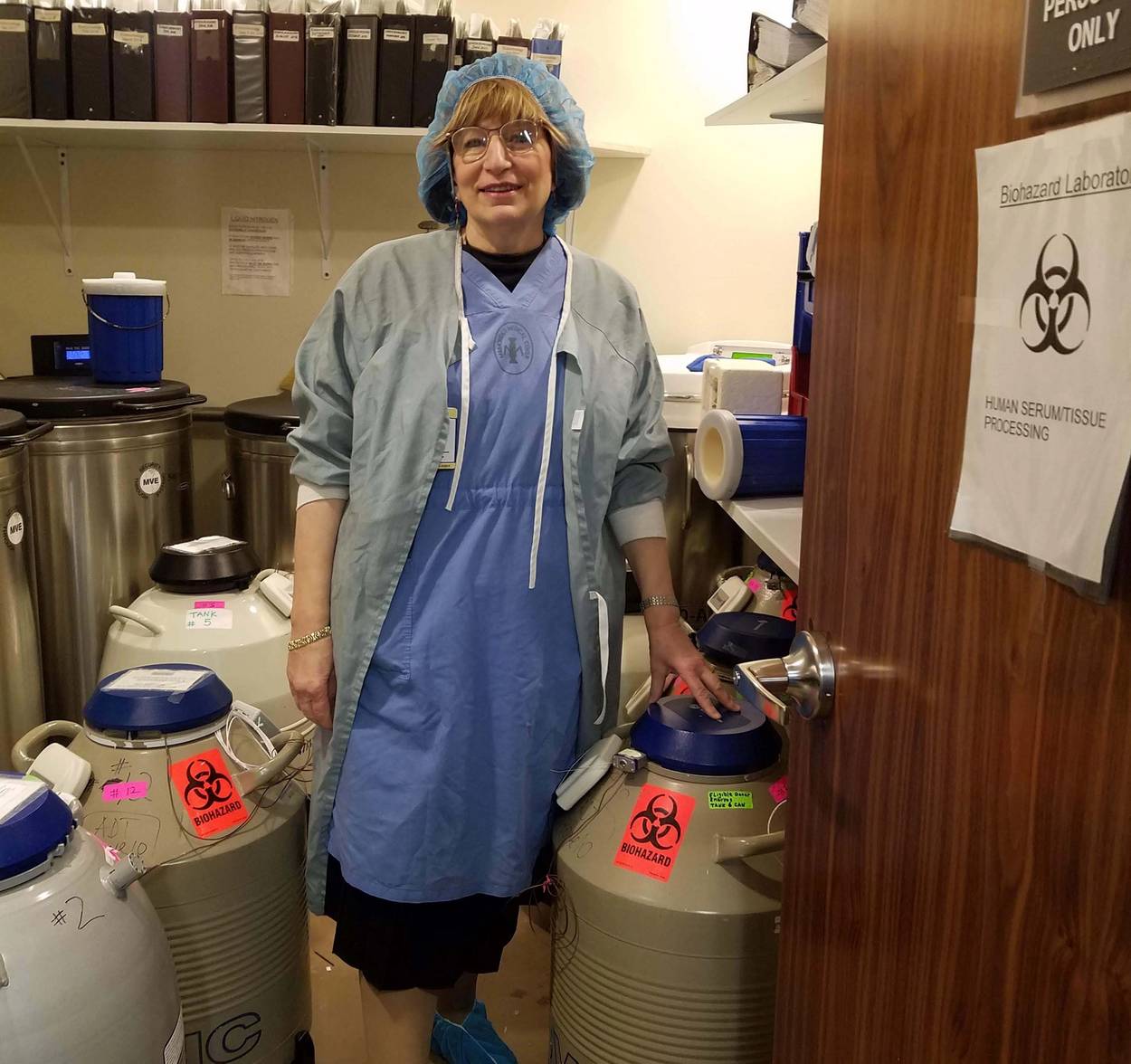

Friedman and I donned the ocean blue scrubs, a cap, gown, and shoe covers that she fished out from her private locker next to the lab.

While there are many women who work as mashgichot, trained and hired by Orthodox fertility organizations like Puah Institute and ATime (which both pay their supervisors), these women are sent ad hoc to witness different procedures for different patients around the country. You could have one woman for retrieval, another for fertilization check, and another for transfer. But Friedman, who only works at Genesis, is paid by her patients to be there for the entire process.

Friedman and I stood in the lab, trying to keep out of the way of the three staff there who were examining eggs, counting the mature ones and discarding the immature ones.

“I know what’s going on the whole time: I always ask the number of how many [eggs] fertilized, how many were discarded, what was ICSI-ed,” she said, referring to the process when one sperm must be injected into an egg, as opposed to millions of sperm being placed in the dish with the egg. (That day I saw some eggs discarded—and it almost broke my heart.)

“They’re not alive, you know,” the embryologist told me after he tossed them in the hazardous waste bin—he must have heard me suck in my breath. I know the eggs aren’t alive, that they are, after all, just cells, cells we women have been losing since the day we are born, and each month during menstruation. But as a former IVF patient who always was on the other side of those lab doors, desperately waiting for a phone call after my egg retrieval to find out how many eggs were mature and how many fertilized, to witness someone discard a woman’s eggs—her hopes for a baby!—made me shed a collective tear for all of us who have done IVF.

Friedman’s job was to ensure her clients’ gametes were identified correctly so that, for instance, Mrs. Goldberg’s egg went into a petri dish marked “Mrs. Goldberg,” and that “Mr. Goldberg’s” sperm was marked with his name, and that “Mr. and Mrs. Goldberg’s” eggs and sperm were combined with each other’s and transferred back to “Mrs. Goldberg’s” womb.

No one at the clinic can touch any of Friedman’s patients’ gametes without her approval. She has her own system: Maimonides-branded tape to place on the embryo incubators (she needs to unseal the incubators for the embryo check every few days) and a small Master Lock on her tank−one of the dozens of tanks in the cryostorage room belongs to her. In it, frozen eggs, embryos and sperm are stored and cryopreserved; even when the tanks need to be refilled with more liquid nitrogen, Friedman has to unlock it. In fact, she has to be there quite a lot—it’s hard for her to estimate how many hours a week because it depends on the number of patients cycling, which procedure must be done (sperm “collection” can take time, and locating sperm from an infertile man can take hours, too).

“This comes first,” she told me, noting that she’s often late to teach sewing class. She still remembers during a snowstorm when she couldn’t get a car service. She only has a flip phone, isn’t on the internet, and therefore can’t get an Uber or Lyft.

“It was snowing and I was crying and I noticed my neighbor has a four-wheel drive so I knocked on his door at 7:30 a.m. and asked him to take me to the clinic.” Her neighbor thought she was nuts—but what can you do?—and on the drive to Genesis asked her how she was going to get home. “Hashem will help me,” she said. Friedman made it in time for the retrieval.

This mother of six, grandmother to more than 30 and great-grandmother to three cannot estimate how many children she’s helped come into the world (the womb?) over a quarter of a century, but she sees a lot of repeat clients for secondary infertility (after one already has a child) and people ask for her personally.

For Friedman and many of the mashgichot, they’re clear it’s not about them. It’s about helping others. Maybe they went through infertility themselves or know someone who did, and they just want to help. “I daven for the people I work with,” Friedman said, talking about the custom of praying on behalf of other people.

God, it used to drive me nuts when religious people would offer to pray for me, as if my infertility was a punishment for leaving my Orthodox roots, and their intercessory prayer would repair it. I guess that’s why, when I was going through infertility from 2011-2014, I’d never even heard of IVF supervision. I definitely would have been against it, judging from my one experience dipping in themikvah ritual bath just to see if it would get me my baby. (It didn’t. I miscarried anyway.) While I found the ritual physically cleansing, (like a spa) and the blessing for fruitfulness emotional, I found the Rabbinate’s intrusion into every crevice of my life infuriating, and I would not have wanted them in my embryology lab either.

But now that I’m almost five years out of my journey, less angry at God (indifferent is my current state), I can see the benefits of IVF supervision.

“We heard all these horror stories of people getting their stuff mixed up. It seemed like a good idea to have an extra set of eyes,” says “Yael,” a 30-year-old modern Orthodox woman from New Jersey who preferred not to use her real name because she was in the midst of an IVF cycle when we spoke.

“They are scary,” says Dr. Goyal, the Genesis lab director, noting that cases like that make all lab directors want to strengthen their “witnessing systems”—the systems in place to prevent lab errors including the chain of custody procedures identifying each person who handled the eggs, sperm and embryos. Most labs have at least two people sign off on every procedure, every time the tissue is handled. Some clinics even use an electronic witnessing system, which Dr. Goyal believes is better suited to “larger clinics.” Genesis only does two or three retrievals a day and never has more than one person’s gametes out in the lab at once, Dr. Goyal says.

While the culture at Maimonides reflects the fact that it’s an historically Jewish hospital sitting in the heart of a heavily Hasidic neighborhood, not all IVF clinics will accommodate a mashgicha in their facilities. For some, it may simply be that they are not familiar with the procedures associated with Jewish law, but for others there are strict rules against allowing noncertified people into their labs, which they may view as a breach of security, or medical protocols, or of both.

Religious women don’t always feel like they have a choice when it comes to using a mashgicha. When Talia Liben Yarmush and her husband, Gabriel, applied to the Bonei Olam organization for financial aid for IVF, they were told that if they were awarded aid, they would have to use an IVF mashgicha.

“We were like, OK, fine,”said Talia, who considers herself denominationally somewhere between Conservative (how she was raised) and modern Orthodox (what her husband and New Jersey shul are). “I was so desperate I would have done anything.”

“Our rabbi said my husband could do it,” Talia said. And so, during their third IVF—they’d already undergone two unsuccessful rounds—Gabriel never took his eyes off their gametes, looking through the lab window to ensure that his sperm was mixed with his wife’s eggs, and, three days later, that the correct embryos were transferred to her body.

Oh, and their rabbi also told her husband to threaten the IVF doctor, and tell him, “I’m going to do a DNA test and I’m going to sue you if there’s a problem.” (Another Hasidic woman told me she also had to do this.) Talia and Gabriel thought it was kind of funny, so instead the husband told their doctor, “I’m supposed to tell you that I’m going to threaten you with a DNA test,” (not quite the same thing).

“I don’t believe in it,” Talia said of the supervision being a necessary check and balance. “But I do understand this is something people really believe is necessary,” she says. That “supervised” round worked, and resulted in her first son, now 8.

Still, a year later, when they did another round of IVF, her husband again acted as supervisor—even though they were no longer obligated to Bonei Olam. “By that time it was more superstition,” Talia says. “We were going to do everything for the fourth cycle that we did for the third.”

That fourth cycle resulted in their second son, now 7.

For “Yael” doing her first IVF retrieval with a religious supervisor brought her peace of mind. The mashgicha met her and her husband at the clinic with sandwiches and water and explained to them what to expect. “It was very comforting to know there was someone who had done this before and knew what was going to happen,” Yael said, noting the last thing she heard before she went under for her egg retrieval was the mashgicha saying “hatzlocha rabah”—good luck.

This article was originally published on July 8, 2020 in TabletMag.com by Amy Klein.

Amy Klein is the author of The Trying Game: Get Through Fertility Treatment and Get Pregnant Without Losing Your Mind. Her Twitter feed is @AmydKlein.